Mining companies operating in remote regions and relying exclusively on diesel power to generate electricity should be considering offshore wind farms as part of an integrated power solution, claims Dr. Dean Millar, who leads Sudbury-based MIRARCO’s Energy, Renewables and Carbon Management team.In a presentation at the 5th annual Mining and Environment International Conference in Sudbury June 27th, Millar pitched offshore wind energy as a possible solution for mining companies operating in remote regions of Ontario and other locations without grid power.

For example, in Ontario’s Ring of Fire, 350 kilometres north of Nakina, Cliffs Natural Resources plans to begin mining a massive chromite deposit by 2015 and may have to rely on an array of diesel generators at least initially to supply 25 MW of power. An underground nickel- PGE mine proposed by Noront Resources a few kilometres away would require 30 MW of power. Millar, MIRARCO Research Chair for Energy in Mining and a professor in the Engineering department at Laurentian University, estimates the discounted cost of diesel power at 33 cents per kilowatt hour. By contrast, the discounted cost of producing electricity from wind turbines in Hudson Bay would be between 13 and 16 cents per kilowatt hour.

High cost of diesel

“Every hour of renewable energy that supplies your mine is one less kilowatt hour that you need to supply from diesel,” said Millar. “It’s the very high cost of diesel in these remote areas that motivates the adoption of renewable energy technologies.

At some point, it might make sense “to bite the bullet” and extend high-capacity energy distribution systems to the Ring of Fire, but as long as a remotely located mine remains off the provincial grid, an integrated solution is far more economical than relying exclusively on diesel.

However, even with grid connectivity, there is an argument to be made for renewables, said Millar.

“There are cost motivations and then there are what I call security of supply motivations.”

DeBeers’ grid-connected Victor Mine in Ontario’s Far North operates on a distribution voltage of 120 kilovolts. “That puts a limit on the amount of electricity you can draw. Secondly, being right at the end of a distribution grid and on a very long limb, you have security of supply issues.”

Wind turbines range in capacity from 2.3 megawatts to 5 megawatts, although there are some commercial prototypes with a rated capacity of 10 megawatts, said Millar.

The limiting factor with wind, however, is that you can’t count on it 100 per cent of the time. Actual capacity, the annual output of a turbine as a proportion of its rated capacity, would ideally approach 35 per cent.

“So, if you have a concentrator with a 30 megawatt demand and you have three wind turbines – each rated at 10 megawatts with a 35 per cent capacity factor – 35 per cent of the demand could be met by the wind turbines,” said Millar.

In February, the Ontario government placed a moratorium on offshore wind projects in the Great Lakes, claiming a need for further research. Offshore wind farm critics who didn’t want their view of the lake spoiled played a role in the government’s policy reversal.

Onshore wind farms and the perceived cost of the feed-in tariffs the province has set for renewable energy have also drawn fire, but Ontarians concerned about the high cost of energy shouldn’t be putting the blame on renewable energy, argued Millar. High feed-in tariff rates, ranging from 13.5 cents per kilowatt hour for onshore wind power to a high of 71.3 cents per kilowatt hour for rooftop solar power, represent a small fraction of the overall price Ontarians pay for electricity, he said.

Scapegoat

The feed-in tariffs are an easy scapegoat, but “the fact is at the moment, the contribution of renewable energy technologies in terms of the amount of power delivered to the provincial grid is so small that their influence on the economics of the market is incredibly modest.”

Producers of renewable energy may be paid 45 cents per kilowatt water, “but that’s not what it costs to produce,” said Millar. Feed-in tariffs for renewable energy are set to provide early adopters with an incentive to innovate and embrace new technologies.

“The most expensive way of producing electricity is nuclear power,” claimed Millar. “Nuclear power plants are expensive to build, they’re inflexible” and because of the economic downturn, consumers are actually paying nuclear power stations not to generate electricity.

“In 2009, there was a significant drop in demand for electricity in Ontario and what the network operator, the Independent Electricity System Operator (IESO), has to do is make sure that, at all times, the aggregate demand for electricity has to meet the aggregate supply.”

Because the demand curve dropped substantially, some of the province’s nuclear generating capacity had to be shut down, but contracts with nuclear power generators stipulate that if the IESO shuts them down, they still get paid, said Millar.

“A lot of people are saying electricity costs are going up because of the green energy subsidies, but the largest chunk of the increase in costs is associated with having to pay for generating capacity that isn’t being used.”

United Kingdom

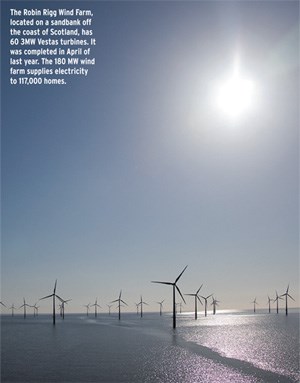

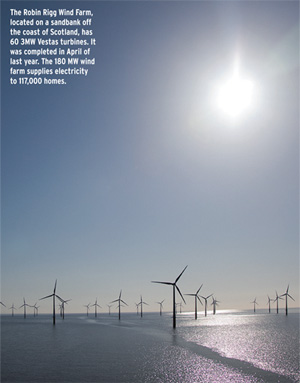

In the United Kingdom, where Millar served as program director for renewable energy and senior lecturer at the Camborne School of Mines prior to coming to Sudbury, there are two gigawatts of installed offshore energy, equivalent to two nuclear power stations.

A concern about wind turbines contributing to bird mortality is wildly overblown, said Millar.

“Detailed studies on migrating birds and their interaction with wind turbines tracked birds as they approached a wind farm, and you know what they did? They flew around them.”

Studies done in Spain and Denmark have demonstrated that on average, wind turbines account for the death of a fraction of a bird per turbine per year, said Millar.

According to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, window strikes and cats are the major causes of bird mortality, together accounting for hundreds of millions of bird deaths per year.