Autonomous tramming, iPads for everyone

The next new mine in the Sudbury Basin will look a lot different than the mines currently in operation, but several cutting-edge technologies being introduced at Vale’s Totten Mine offer a preview of mining in the digital age.

“We’re building the future here, not only for Totten, but creating a future for Sudbury and transforming how we’re mining,” said mine manager Derek Kulyski.

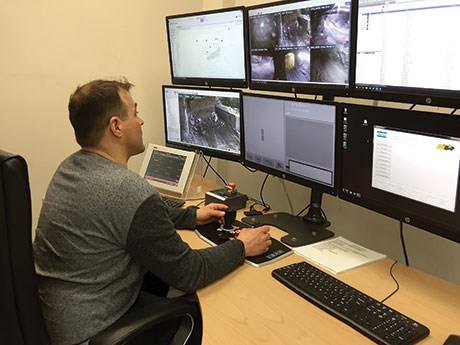

In the control room on surface at Totten, Ryan Joly scoops up a bucket of muck from a drawpoint 3,800-feet underground, presses a button and watches as the eight-yard Atlas Copco scoop autonomously proceeds to a grizzly some distance away, dumps its load and autonomously returns to the drawpoint.

“Right now, we’re not a 24-hour operation,” said Kulyski. “We’re a 21-hour operation, so there’s a gap of time in between shifts when no production occurs underground. We have to clear the gases from blasting, and to be able to have a piece of equipment that is productive and operating from surface during that time adds a lot of value.”

Operating a scoop from surface is also a lot safer, said Kulyski, as Joly isn’t exposed to dust and diesel fumes or the risk of musculoskeletal injuries. With access to cameras in the work area as well as on the scoop itself, he has better visibility than if he was sitting in the cab.

Using ISAAC vehicle telemetry from Newtrax Technologies, Joly can monitor tire pressures, temperature, battery voltage and other diagnostics in real time on a screen immediately in front of him, said Ozzy Flores, Totten’s automation supervisor.

Using ISAAC to perform data analytics on mobile and stationary equipment, mechanics can be more proactive and develop condition-based maintenance schedules instead of relying on calendar-based schedules

The transfer of muck from the drawpoint to the grizzly has to occur every day and would normally be done during a regular shift. By taking advantage of the three-hour window between shifts to effect the transfer from surface, men and machines are freed up to be more productive the rest of the day.

In a two and a quarter hour period, Joly can transfer 41 buckets of muck, equating to 600 tonnes of material.

He can also record new routes for autonomous tramming using Epiroc’s Route Manager software and two lasers on the scoop.

From the grizzly, the muck descends to a coarse ore bin, which feeds Totten’s crusher.

Aside from the scoop, Joly also operates a Simba in-the-hole production drill from his work station in the control room.

Totten is also moving forward with short interval control capability made possible by mine-wide WiFi and tracking technology that offers management data to make decisions in real time.

If a jumbo is unable to drill because of a problem in one heading, explained Kulyski, management can redirect it to another location.

“At some point in 2019,” predicts Kulyski, “every employee at Totten will have an iPad, so just like you grab your cap lamp, you’re going to grab your iPad.

“We started a trial with our maintenance people and it has been very, very successful. Our maintenance people do a lot of troubleshooting, so with an iPad, they can see where the equipment is, they can call up the equipment history, look at the work orders, see when the last service was done and what parts were changed. They can access schematics, and equipment drawings instead of having to return to the shop and search through hard copy manuals.”

They can also make a call to a peer, supervisor, or OEM tech support, access YouTube how-to videos on the Internet, take photographs and create work orders.

“In the future, iPads can be used to communicate where personnel need to be and what safety information they should be aware of,” said Kulyski.

Rather than purchase super expensive ruggedized tablets that can cost anywhere from $6,000 to $7,000, Totten uses $500 iPads that are carried in lunchboxes or pouches.

Totten isn’t the only Vale mine in the Sudbury Basin introducing new technology, Kulyski is quick to point out.

Coleman Mine has the company’s first battery-powered piece of equipment undergoing trials, Copper Cliff Mine is revolutionizing the supervisory role with the aid of digital technology and, like Totten, Creighton Mine is using teleremote and autonomous mining technology to extend production into the three hour period between shifts when the presence of blasting gases makes it impossible to operate any other way.

“There’s always a nervousness around implementing automated technology because people are afraid that robots are going to be doing their job, but we’re actually going to be able to create jobs,” said Kulyski.

“We have to be able to significantly drop our operating costs to be profitable in all price cycle environments. The technology we’re proving here can go into a place like Kelly Lake (phase 2 of Vale’s Copper Cliff expansion project). We could design a mine at Kelly Lake with 140 people that will never happen because it’s not profitable, or we can design a mine of the future with 70 people. Kelly Lake is just one example. We have a lot of known deposits out there that are lower grade and we need a fundamental shift in the way we mine to be able to bring them into production.”