Cobalt price has soared from $22,000/tonne in February 2016 to $80,000 per tonne in January

Flush with cash from a year-end share offering, First Cobalt Corp. is exploring the Cobalt mining camp like it’s never been explored before.

“We’ve never gone looking for cobalt for cobalt’s sake,” said First Cobalt president Trent Mell. “Having started to do that this year, I’m seeing a lot of opportunities.”

The company raised $30 million in December. With a large land package stretching from Cobalt to Silver Centre, including 50 former silver mines, a mill and refinery, First Cobalt is hunting for a mineral that’s tripled in value since 2015, largely due to anticipated demand from electric car makers.

In addition to being used for jet engines, gas turbines and specialty steel, cobalt is used to make cathodes in lithium-ion batteries. While portable power tools, laptops, phones and tablets have accounted for much of the demand for lithium-ion batteries, emerging technologies such as battery-powered mining equipment, electric transport trucks and buses are increasing that demand. Automakers are investing billions as they race to get new battery-powered vehicles on the market.

The Democratic Republic of the Congo produces about 60 per cent of the world’s supply of cobalt, but its market dominance may fade as manufacturers around the world press for stable, secure and ethically-sourced supplies of the mineral.

“The world is going to be surprised by what Canada can contribute to the cobalt market,” said Mell, former president and CEO of Falco Resources and former vice-president at Aurico Gold. First Cobalt assembled its large land package by joining forces with two other junior mining companies. It’s merger with CobalTech Mining Inc. brought a mill into the equation while its merger with Cobalt One Limited included a refinery with facilities and permits to produce battery-grade materials.

It just made sense to merge the three companies, Mell said. “A bunch of us got in a room and we recognized that if we’re going to be successful as a cobalt company we need scale. So, by putting the three companies together we created the world’s largest cobalt exploration company by market cap,” Mell said. “All of our land claims were contiguous, so perhaps as important as the market cap size, we’ve basically locked up 45 per cent of the historically prospective claims that make up what was Silver Centre and Cobalt.”

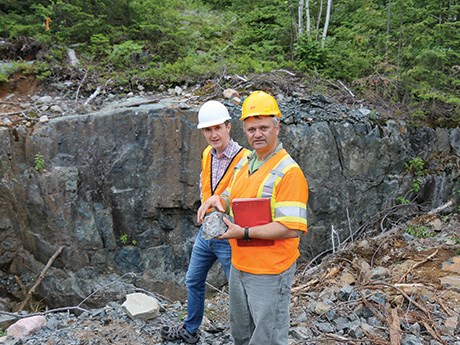

The company built its exploration team around geoscientist Dr. Frank Santaguida as vice-president of exploration, and exploration manager Jason Ricard, previously a senior geologist at Goldcorp Inc.

It sampled and assayed waste rock from long-dormant silver mines. “We have three one-tonne samples of rock that we’re sending to three outfits and we’ll have them tested,” Mell said.

The company’s 100 tonne-per-day mill might be used to process waste rock. “We’ve had some really interesting grades,” Mell said, “so the mill could come in if we were to look at reprocessing some of these stockpiles for some early cash flow.”

Cobalt One Limited bought the Yukon Refinery in North Cobalt for $5 million in early 2017 at a time when it was discussing a merger with First Cobalt. Built about 20 years ago, the refinery had a checkered past, in part because it never had a source of dedicated feed, Mell said. It had been on care and maintenance since 2015.

The batch autoclave refinery, originally built to handle 12 tonnes per day, was upgraded with a second autoclave to 24 tonnes per day, but was never put back in production, Mell said. “We’re probably going to double it again,” he added. The refinery has all the necessary permits and a proven flow sheet to process ore containing arsenic. “To my knowledge this is the only permitted cobalt refinery capable of producing battery materials in North America, so it’s a pretty important asset,” Mell said.

In August, First Cobalt began diamond drilling to test veins at past-producing mines in Silver Centre. This initial 6,366-metre program completed 61 holes. Early assays confirmed the presence of three cobalt bearing veins southwest of the Keeley Mine. In 2018, Mell expects the company will do 20,000 or 30,000 metres of drilling, most within 200 metres of surface. “My hope would be that by the end of year we’ll start to zero in on where in the camp we want to focus our efforts.”

In addition to diamond drilling, compiling assays and developing an understanding of regional faults and formations that control mineralization, the company intends to undertake a major exercise in data compilation, Mell said. “We’ve got boxes and boxes and terabytes of information that needs to be compiled and that’s going to be one of the interesting things next year that we’re going to do. We’re going to team up with some tech companies and bring artificial intelligence into the camp,” he said.

“Experience tells us that old mines can often be reinvented into new mines with the benefit of the passage of time and the benefit of new technology and mining methods,” Mell said.

Although Cobalt was renowned for high-grade silver, it also produced about 50 million pounds of cobalt, worth more than $1.5 billion at today’s prices. “The focus back then was on the veins and specifically the silver-rich carbonate veins. We also know now, looking at the records we have that some of these smaller, failed silver mines were actually carbonate veins that were high in cobalt content,” Mell said. “So, we’re going back through this with a bit of a different perspective. We want to focus on cobalt as the target.”

First Cobalt is looking for bulk mining opportunities. “We’re not looking to mine high-grade underground veins of any type. That’s small and it’s tough to do,” he said. “If you can mine these as open pits or eventually underground deposits then I think that’s the way of the future.”

Data compilation will help develop a clearer picture of mineralization in the camp. “That’s where computers, algorithms and artificial intelligence come in – not to replace the judgment of geologists but to help them out, identify trends and patterns and opportunities. I think you’ll see us talk a fair bit about that as we enter next year. Technology can help us get to an answer faster than just the drill bit.”

.jpg;w=120;h=80;mode=crop)